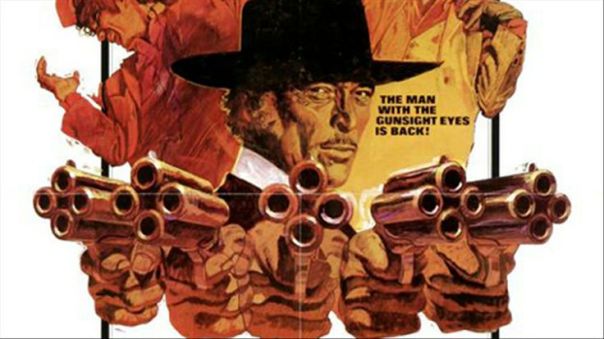

Spaghetti Westerns Unchained – The Good, the Bad and the Guilty Pleasures

‘Django Unchained’ (2012), Tarantino’s Academy Award winning and hugely profitable homage to the Spaghetti Western (with a worldwide gross of $425 million plus DVD and download sales) has proven what we SW aficionados have always known – that Italian westerns are deliriously enjoyable, seriously addictive and offer more bang for your buck, literally, than any other genre.

The New Era of Silent Movies, Part I

“There’s so many great films that you feel like you’ve seen everything, but then you crack open a vault of amazing stuff.” Rob Zombie

The recent release of several fully restored classic films from the 1920s on Blu-ray suggests that silent movies are no longer a niche market for the cineast and art house audience, but are a core element of the DVD retail market with an increasing share of disc sales. And with sell-out screenings for the recent theatrical reissue of the influential German expressionist classic ‘The Cabinet of Dr Caligari’ (1920), F. W. Murnau’s iconic ‘Nosferatu’ (1922), Buster Keaton’s comic masterpiece ‘The General’ (1926), Raoul Walsh’ opulent ‘The Thief of Bagdad’ (1924), and Fritz Lang’s dystopian SF epic ‘Metropolis’ (1927), silent cinema appears to be enjoying a real revival.

The Haunting of Charles Dickens

The Victorians were very fond of ghost stories and the most popular authors of the period relished competing with one another to see who could make their reader’s flesh creep the most. One of the era’s best loved storytellers was Charles Dickens, though surprisingly the author of ‘A Christmas Carol’, ‘Oliver Twist’ and other classics was not a believer in the supernatural. In fact, Dickens was a hardened skeptic until he had a disquieting paranormal experience of his own…

The Man Who ‘Saw’ The Ripper

It is not an exaggeration to say that today psychics are consulted on an almost routine basis when the authorities have exhausted all conventional avenues of investigation. But in Victorian England ‘spiritualists’, as they were then known, were regarded at best as being either a novelty Music Hall act or at worst, fraudsters preying on the weak-minded and bereaved. The fact that clairvoyant Robert James Lees had been consulted on several occasions by Queen Victoria did not, however, make him a credible witness as far as Scotland Yard were concerned. When Lees offered his services as a psychic sleuth it is said that they laughed him out of the building. However, if the account published by ex-Scotland Yard officer Edwin T. Woodhall (author of ‘Secrets of Scotland Yard’) is to be believed, they were soon to regret their rash decision.

Airship Pirates and Clockwork Quartets

It may be of little concern to the bureaucrats who drew up the Trade Descriptions Act, but it’s an undeniable fact that there isn’t much punk in steampunk. At least not of the three-chord thrash variety spat out by the snotty, glue sniffing, safety pin and spiky hair, pogo-till-you-puke brigade who stormed the barricades back in ’76, or ‘Rock’s Year Zero’ as the NME would have it. Back then it was ‘Anarchy In The UK’ and the wholesale slaughter of the dinosaurs of corporate rock. Now it’s more like anachronistic fashion accessories in the UK and US as the likes of Abney Park, Sunday Driver and Vernian Process describe a dystopian fantasy world through rose-tinted goggles with a sentimentality that would make the late Bill Grundy doubt he could goad them in to saying something risqué about Queen Victoria.

It may be of little concern to the bureaucrats who drew up the Trade Descriptions Act, but it’s an undeniable fact that there isn’t much punk in steampunk. At least not of the three-chord thrash variety spat out by the snotty, glue sniffing, safety pin and spiky hair, pogo-till-you-puke brigade who stormed the barricades back in ’76, or ‘Rock’s Year Zero’ as the NME would have it. Back then it was ‘Anarchy In The UK’ and the wholesale slaughter of the dinosaurs of corporate rock. Now it’s more like anachronistic fashion accessories in the UK and US as the likes of Abney Park, Sunday Driver and Vernian Process describe a dystopian fantasy world through rose-tinted goggles with a sentimentality that would make the late Bill Grundy doubt he could goad them in to saying something risqué about Queen Victoria.

Paul interviews The Velvet Underground (1985)

In 1985, just prior to the release of the ‘VU’ album (a collection of previously unreleased tracks recorded in 1969 and intended for their fourth album), I had the privilege of interviewing Nico, Sterling Morrison and Maureen Tucker for a national Sunday newspaper. At the end of each interview I mentioned that I was preparing a new album (to follow ‘Burnt Orchids’) and asked if they would consider playing on it, if I could get the multi-track tapes shipped to the States. They agreed and Sterling seemed particularly keen as he was eager to get back into music after taking time out to study for a university degree. I remember that he was very complimentary about my songwriting after he heard the tapes (backing tracks with guide vocals, not demos) and in a couple of telephone conversations he mentioned that he found the structure of the songs unusual and that interested him. But the tape formats were not compatible with the equipment in the studio he was using at the time and I let the project lapse, assuming that we would sort it out at a later date. I even had a letter from his attorney asking me to give him extra time, but I had an offer from UK psych label Bam Caruso and needed to deliver an album by a certain date, so I shelved the songs I had written for the VU and moved on. Then, sometime later, Sterling died and so did Nico.

In 1985, just prior to the release of the ‘VU’ album (a collection of previously unreleased tracks recorded in 1969 and intended for their fourth album), I had the privilege of interviewing Nico, Sterling Morrison and Maureen Tucker for a national Sunday newspaper. At the end of each interview I mentioned that I was preparing a new album (to follow ‘Burnt Orchids’) and asked if they would consider playing on it, if I could get the multi-track tapes shipped to the States. They agreed and Sterling seemed particularly keen as he was eager to get back into music after taking time out to study for a university degree. I remember that he was very complimentary about my songwriting after he heard the tapes (backing tracks with guide vocals, not demos) and in a couple of telephone conversations he mentioned that he found the structure of the songs unusual and that interested him. But the tape formats were not compatible with the equipment in the studio he was using at the time and I let the project lapse, assuming that we would sort it out at a later date. I even had a letter from his attorney asking me to give him extra time, but I had an offer from UK psych label Bam Caruso and needed to deliver an album by a certain date, so I shelved the songs I had written for the VU and moved on. Then, sometime later, Sterling died and so did Nico.

It was not until last year, 27 years(!) after writing those songs that I thought of digging them out, dusting them off and recording them as I had been itching to get back to playing with a rock band after a year spent creating a solo acoustic project (‘Grimm’). The resulting album, ‘Bates Motel’ (which also includes songs written for a John’s Children reunion album at the invitation of frontman Andy Ellison), is released next month on the German label Sireena Records.

Let the Blood Run Red (1983, Part 1)

Paul Roland braves the curse of the critics to trace the history of HAMMER – the house of horror

Prologue

During the early 1980s I was writing for a number of film and music magazines and, being a huge horror movie buff, I naturally took the opportunity to suggest a Hammer feature at one of Kerrang’s weekly editorial meetings. It is basically an introductory overview of the studio’s horror output and for reasons of space omits reference to a couple of my favourite Hammer filmsm ‘The Witches’ and ‘Captain Kronos – Vampire Hunter’, but for those who are not hardcore Hammer fans it may be of interest for the brief quotes from Christopher Lee and the various Hammer ‘House’ directors. (My interview with Peter Cushing can be found elsewhere on this site).

The New Era of Silent Movies, Part III

The enviable state of Lloyd’s legacy is the exception rather than the rule as silent movies used nitrate film stock which was highly inflammable and prone to deterioration if not stored in ideal conditions. Prints struck from nitrate negatives imbued the image with a lustrous sheen (from which the term ‘the silver screen’ was derived) but they proved to be unstable.

Sadly, only 14% of the 11,000 films produced in the US between 1912–1929 have survived in their original 35mm format (source: Library of Congress) and of these 5% are incomplete. In all, 11% of the remainder exist in inferior formats such as 16mm or in foreign language prints (which invariably used different shots as the export version would be filmed by a second camera simultaneously or subsequently if a different cast were used).

Unfortunately, a curator of one of the largest libraries of silent movies in America is said to have told her staff that if only one can of nitrate film showed signs of deterioration they were to destroy every reel of that particular film, rather than splice out and dispose of the affected section. For this reason numerous films by major studios that were entrusted to this archivist have been lost forever.

Ernst Sezebedits, Chairman of the F.W. Murnau Foundation, concludes that there is no choice but to put all their resources into saving these films before it is too late:

“If these films are not adapted to digitization now, they will simply no longer be visible. That is, this film heritage will disappear from the world.”

Essential Silent Movies

‘The Cabinet of Dr Caligari’ 2014 restoration (Kino), Robert Wiene

‘The Man Who Laughs’ (Kino), Conrad Veidt

‘Metropolis -Reconstructed and Restored’ (Eureka), ‘Spione’ (Eureka), and ‘Dr Mabuse – The Gambler’ (Eureka), Fritz Lang

‘Pandora’s Box’ (Second Sight) and ‘Diary of a Lost Girl’ (Eureka Masters of Cinema) Louise Brooks/G.W. Pabst

‘Faust’ (Eureka 2 disc edition), ‘Nosferatu’ 2013 restoration (Eureka), ‘The Last Laugh’ (Eureka) and ‘Sunrise’ (Eureka), F.W. Murnau

‘L’ Argent’ (Eureka) Marcel L’ Herbier

‘Iron Mask’ (Kino) and ‘The Thief of Bagdad’ (Cohen Film Collection), Douglas Fairbanks

‘Vampyr’ (Eureka) and ‘The Passion of Joan of Arc’ (Eureka), Carl Theodor Dryer

‘The General’ 2 Disc (Cinema Club), ‘Sherlock Jnr’ (Kino) and ‘Steamboat Bill Jr’ (Kino), Buster Keaton

‘The Gold Rush’ (Criterion Collection) Charlie Chaplin 1925 original is preferred to the 1945 edited version with voice-over made by Chaplin in order to renew his copyright.

‘The Definitive Collection’ (Studio Canal), Harold Lloyd

Books

Kevin Brownlow ‘The Parade’s Gone By’ (University of California Press) and ‘Hollywood-The Pioneers’ (Harper Collins)

James van Dyck Card ‘Seductive Cinema: The Art of Silent Film’ (University of Minnesota Press)

Grieveson and Kramer ‘The Silent Cinema Reader’ (Routledge)

Paul Merton ‘Silent Comedy’ (Arrow)

Joe Franklin/William K. Everson ‘Classics of the Silent Screen’ (Citadel Press)

Documentaries

‘Hollywood’ (You Tube)

Paul Merton’s ‘Silent Clowns’ (You Tube)**

‘Unknown Chaplin’ (Network)

‘Harold Lloyd ‘The Third Genius’ (RTM)

‘Buster Keaton-A Hard Act To Follow’ (Network)

Read: The New Era of Silent Films Part I and Part II

**A special mention, too, for pianist Neil Brand who has been introducing UK audiences to the delights of silent cinema with his one man show ‘The Silent Pianist Speaks’ and accompanying comedian Paul Merton’s ‘Silent Clowns’ tour.

The New Era of Silent Movies, Part II

“It’s almost like you have to think differently than you do with regular movies… It’s such a different rhythm. It’s such a different experience.” Rob Zombie

One of the most impressive and extensive restorations to date was that lavished upon ‘Nosferatu’ (1922), which is considered to be the first genuine horror film and one of the most unsettling examples of the genre thanks to the skin-crawling appearance of Max Schreck as the cadaverous vampire, Count Orlock.

Murnau’s gothic fairy tale was thought to have survived only in well-worn duplicate prints after Bram Stoker’s widow won a legal battle to suppress this unauthorized adaptation of her husband’s 1897 novel ‘Dracula’. All existing prints were believed to have been destroyed along with the original negative. It is nothing short of a miracle that the film has been restored to the extent that it has by the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Stiftung (F.W. Murnau Foundation), giving the impression that the latest release had been sourced from a first generation print. In fact, it was pieced together from multiple sources which had suffered varying degrees of ill-treatment over the years. Such improvements and enhancements do not simply offer a more pleasurable viewing experience; they effectively dissolve the barrier between the viewer and the images on screen to allow greater engagement with the characters and give the film an immediacy that belies its age. It is no longer an artefact but has been brought back to life.

Director Robert Wiene’s ‘The Cabinet of Dr Caligari’ (1920) is another historically significant film that has been saved from the ignominy of the bargain bin by an extensive restoration. Although only nominally a horror film, it establishes several key elements of the genre, most notably the inclusion of an archetypal ‘mad doctor’ (Werner Krauss, who is revealed to be the director of a madhouse in the film’s final scene) and his homicidal ‘creature’ (Cesare, the somnambulist played by Conrad Veidt) who abducts the heroine and carries her off across the rooftops.

With its bizarre sets of painted shadows and forced perspective suggestive of a madman’s vision, ‘Caligari’ is one of the most striking examples of German expressionism. Those who have seen it in its numerous pre-restoration editions will find it hard to believe that the stunning new edition by the Murnau Foundation is the same film.

Influence of the Early German Horror Films

Both ‘Nosferatu’ and ‘Caligari’ continue to exercise a fascination for modern audiences who are now more likely to explore related releases such as the supernatural fantasy ‘Warning Shadows’ (1923), Paul Leni’s atmospheric haunted house comedy ‘The Cat and the Canary’ (1927), ‘The Penalty’ (1920) with Lon Chaney Snr as a crippled crime lord and Wiene’s ‘The Hands of Orlac’ (1924). The latter stars Veidt in the tale of a pianist who fears he has inherited homicidal tendencies after having the hands of a murderer grafted onto his amputated stumps. Such morbid subjects were evidently acceptable to audiences before the Hays code of 1930 prohibited graphic violence, drug addiction and explicit allusions to sexual intercourse to be depicted on screen.

But if any film is likely to convert the skeptical to the neglected art of silent film, it is the macabre period costume drama ‘The Man Who Laughs’ (1928) again with Conrad Veidt, this time cast as a clown bent on revenge after being gruesomely disfigured as a child by a sadistic monarch. The story was based on a novel by Victor Hugo and, although set in 18th century France, the German director Paul Leni blended Grand Guignol with German expressionism to produce a truly remarkable and richly atmospheric film that deserves to be better known and more frequently viewed.

The perennial popularity of these classic early horror films is proof that the language of silent cinema remains truly international, but they only represent a small portion of the treasures on offer. New converts to silent cinema will discover that they are able to enjoy films made in a number of countries where the new medium was finding its most eloquent expression.

In Russia Sergej Eisenstein was perfecting the art of film as propaganda and developing the technique of montage for ‘Battleship Potemkin’ (1925), ‘Strike’ (1925) and ‘October 1917’ (1927); in Japan Yasujiro Ozu was assimilating American influences in his earliest forays into the medium that he would come to master, in France Marcel L’Herbier was using film to portray psychological conflict in his anti-capitalist drama ‘L’argent’ (Money, 1928) and in Denmark Carl Theodor Dreyer was pioneering the close-up, low camera angles and harsh natural lighting to convey the emotional turmoil of his leading actress in ‘The Passion of Joan of Arc’ (1928). Also in France, Abel Gance devised and utilized many innovative techniques in his historical epic ‘Napoleon’ (1927) that gave lie to the impression that silent films were static and unsophisticated, while in Germany Murnau, Pabst and Lang were being celebrated for films noted for their innovative optical effects, technical brilliance, fluid camera movements and naturalistic acting. It was these achievements which subsequently brought their directors to the attention of the Hollywood studios where other European émigrés such as Billy Wilder, William Dieterle, Josef von Sternberg, Ernst Lubitsch, William Wyler, and Erich von Stroheim had found employment after fleeing Nazi oppression.

At Fox Murnau was to make what is generally acknowledged as one of the crowning achievements of the silent era, ‘Sunrise’ (1927) for which he and his technicians devised innovative in-camera effects and other techniques such as using children and models in the middle distance to create the illusion of a large city on a comparatively small set. A 2012 Sight and Sound magazine poll for the BFI named it as the fifth best film in the history of motion pictures and time has not dimmed or devalued its visual and emotional impact.

It is worth mentioning that Murnau also made the only silent movie that did not include the customary intertitles (save one to justify the upbeat epilogue). ‘The Last Laugh’ (1924) stared Emil Jannings as a hotel doorman who cannot face the humiliation of being sacked from his job and resorts to stealing his own uniform so he can continue the pretence. It remains an extremely moving film and testament to the potency of the silent image.

“When you see a silent movie, you understand everything that’s going on from the images because the images are so strong.” Monica Bellucci (Italian actor)

Not all silent movies have aged as well, however. ‘The Big Parade’ (1925), directed by King Vidor and starring John Gilbert, was the biggest grossing film of the silent era netting some $20 million (equivalent to $250 mio. today), but it is hampered by a sickly sweet romantic subplot and its battle scenes were bettered by both ‘Wings’ (1927) and ‘All Quiet On The Western Front’ (1929). ‘Wings’ was helmed by director William Wellman who drew on his own combat experience for the aerial dogfights and was justly rewarded with the first Academy Award for Best Picture. Lewis Milestone’s anti-war film was originally released in a silent version with synchronized sound, but converted to a talkie before re-release in 1939.

Anyone who imagines that films of the period were static tableaus or elaborate pantomimes animated in fits and starts by actors favouring exaggerated gestures from the Sarah Bernhardt school of barnstorming melodrama will be impressed by the naturalistic performances, fluid camera work, optical effects and opulent sets that feature in the aforementioned films as well as the prestige pictures produced by the major Hollywood studios toward the end of the 20s.

If you doubt it, watch any one of the extravagant spectacles staring the athletic Douglas Fairbanks whose ‘Robin Hood’ (1922) qualified as the second most expensive movie of the silent era. (It was beaten only by the 1925 version of ‘Ben-Hur’ staring Ramon Navarro, which is justly celebrated for its exhilarating chariot race, even though we all know who wins before it even begins).

Fairbanks, whose ‘Mark of Zorro’ (1920) saw the big screen debut of the original Dark Knight and whose skill with a whip presaged Indiana Jones, never ran when he could leap and never leapt when he could fly—as he did most convincingly in the silent screen’s spectacular Arabian nights fantasy ‘The Thief of Bagdad’ (1924). The latter’s sets (designed by William Cameron Menzies) and special effects are still impressive in the age of CGI where armies of computer-generated warriors are commonplace, but silent film buffs swear they are no substitute for the massed crowds of costumed extras that were regularly mustered for silent epics, or the massive sets which only the Hollywood studio system could put at its directors’ and stars’ disposal.

Directors such as D.W. Griffith, Cecil B. deMille and Erich von Stroheim made outrageous demands in the name of entertainment and authenticity, which drove their studios to the point of financial ruin. Griffith’s ‘Intolerance’ (1916), for example, claimed the lives of several extras who were drowned when gallons of water flooded the set during the destruction of Belshazzar’s palace, while von Stroheim insisted on filming the climactic scene of ‘Greed’ in the searing heat of Death Valley which led to severe cases of heatstroke among his cast and crew. Stroheim was a notorious martinet and a profligate, who once demanded that the costume department furnish the male cast members of a period drama with silk underwear embroidered with the correct coat of arms on the pretext that they would play their roles more efficiently if they knew their uniforms were authentic down to the last detail. Thanks to DVD his lost masterpiece ‘Greed’ survives in a recently reconstructed four hour director’s cut which the panic stricken studio had reduced to two in the vain hope of reclaiming some of its crippling costs.

The name of Cecil B. deMille is synonymous with excess, but he trumped himself by bringing real lions on the set for a scene in ‘Male and Female’ (1919) during which Gloria Swanson was required to feign unconsciousness while a fully grown lion held her down with one paw on her bare back. DeMille himself kept a loaded revolver at his side during that particular scene while the beast’s keepers cracked their whips off camera to goad it into roaring on cue.

It was Swanson who summed up the allure of the silent era when she played faded screen diva Norma Desmond in Billy Wilder’s elegy to Hollywood’s golden era, ‘Sunset Boulevard’ (1950). During a screening of one of her own movies (‘Queen Kelly’ directed by Erich von Stroheim), Norma leaps to her feet and caught in the beam of the projector delivers the classic line, “We didn’t need dialogue. We had faces then.”

She was doubtless referring to the enigmatic Greta Garbo and heart throb Rudolph Valentino, but while they are now regarded as icons of another more innocent age, comedian and director Buster Keaton remains perennially popular and his films among the most watchable and enjoyable of any period. Keaton incidentally made a fleeting appearance in ‘Sunset Boulevard’ playing one of Norma’s aging friends, referred to rather disparagingly in the film as her ‘waxworks’. His dead pan expression earned him the sobriquet ‘The Great Stone Face’ and made him a worldwide star on a par with Chaplin, but while Chaplin’s art now seems compromised by cloying sentimentality, Keaton’s sardonic sensibility and restless ingenuity have ensured that the best of his surviving films retain their ability to entertain and amaze. Keaton, a former child acrobat, risked his life on more than one occasion for the sake of a gag, the most famous being when he narrowly escaped being flattened by the front of a two-storey timber house during the hurricane sequence in ‘Steamboat Bill, Jr.’. The house collapses leaving Keaton framed in the narrow window, a gap of mere inches on either side.

He also created a dazzling sequence for ‘Sherlock, Jr.’ (1924) in which he played a cinema projectionist who dreams himself onto the screen and through a series of precarious situations as the scenery changes in quick succession. Fortunately, most of Keaton’s full-length features survive intact and have been lovingly restored including ‘The General’ (which has been ranked as one of the finest films ever made by both the AFI and the BFI), although a number of his equally inventive shorts are in poorer shape and several are missing key sequences.

The only serious rival to Keaton and Chaplin in the comedy stakes was bespectacled comedian Harold Lloyd who was known as ‘The Third Genius’. Lloyd shrewdly retained the rights to all of his films and preserved them for posterity along with home movie footage and thousands of photographs so that when his estate authorised their release on DVD they were in pristine condition and could offer copious bonus features. But while he was happy to give his fans a recorded tour of his magnificent Hollywood estate, he was more guarded when it came to the secrets that had astonished audiences in his most popular film, ‘Safety Last’ (1923). For the climactic scene Harold’s character scales the outside of a department store after a human fly that he had engaged for a publicity stunt fails to show up. His gravity defying stunt – which involved dangling from a clock face (a scene that was replicated in Scorsese’s ‘Hugo’) – became one of the iconic images of the silent era and also one of the best kept secrets in movie history.

It was not until 1981, a decade after his death, that the makers of the Thames Television documentary ‘Hollywood’ revealed that it was essentially an optical illusion created by constructing a false section of the exterior of the department store on the roof of a seven-storey building at 908 South Broadway. By clever placement of the camera Lloyd was able to scale the new structure overlooking downtown Los Angeles while in fact being only a few feet from the ground. Nevertheless, it was still a physically demanding role as Lloyd had lost his thumb, index finger and half of the palm of his right hand in an earlier accident when a prop bomb that had been packed with real explosive had detonated prematurely.

Read: The New Era of Silent Films Part I, Part III (with essential filmography, bibliography, and documentaries)

The Nuremberg Rituals – An invocation of Mars

In 1834 Heine published Religion and Philosophy in Germany, in which appeared this prophetic warning:

“But most of all to be feared would be the philosophers of nature were they actively to mingle in a German revolution, and to identify themselves with the work of destruction. […] the Philosopher of Nature will be terrible in this, that he has allied himself with the primitive powers of nature, that he can conjure up the demoniac forces of old German pantheism; and having done so, there is aroused in him that ancient German eagerness for battle which combats not for the sake of destroying, not even for the sake of victory, but merely for the sake of the combat itself.”

The Houseguest (a playlet)

Cast:

AN ELDERLY ARISTOCRAT

HIS YOUNGER MALE HOUSEGUEST AND BIOGRAPHER

ACT I

SCENE ONE

(THE MALE HOUSE GUEST SITS IN AN ANTIQUE CHAIR AND DOES NOT SPEAK THROUGHOUT, WHILE THE ARISTOCRAT PACES ACROSS THE STAGE DELIVERING A MONOLOGUE. WHEN THE HOUSEGUEST IS NOT ACTIVELY LISTENING OR ACKNOWLEDGING WHAT IS BEING SAID, HE WILL BE WRITING DOWN WHAT HE HAS HEARD)

ARISTOCRAT

Tell me, my friend, have you ever loved someone so completely, so passionately that when they departed this life, you wished you had the courage to follow them, though you dreaded what might await you? I am not ashamed to confess that I have loved this intensely, with every fibre of my being. And though the loss of such a love has brought me acute anguish, the like of which you cannot imagine, I have not regretted having loved and lost, as the poets would have it.

I can’t imagine anyone having been as ill-used as myself, but I want you to know that there was a time when I knew true happiness and the memory of that blissful union is what has sustained me. Though I had lived a full twenty years before my beloved and I met, it was only from that day that I felt truly alive. Before then I merely existed.

Love is the very reason for living. Is it not? Without companionship, affection and the unspoken understanding that binds two souls who are in complete accord, we are merely sleepwalking through life. And I should know, for I have been in that wretched state now for what seems like an eternity. And yet, I could not follow the one who was so dear to me into the unknown. The one who gave meaning to my life. Oh, believe me, I tried. More than once during those empty days that followed my bereavement when I thought that sorrow weighed upon me so heavy that it would stop my heart from beating and the blood from coursing through my veins. No living thing should have to endure being left alone in the dark after the very breath of life has been extinguished; when all that one has believed in ceases to have significance, leaving only memories. And what are those but vapour, a vague impression, a vivid dream that is glimpsed and is gone?

With their parting the loved one ceases to be real. Like those words you are writing so furiously lest you miss every element of my confession. And yet, despite my grief I could not summon the courage to end it. At the critical moment I could not make that leap of faith into the abyss.

It was not a question of fear or of belief. For if there is a heaven—and we have only the word of the clergy that there is (and this from those who do not seem over eager to forgo their terrestrial wealth and power for the promise of celestial reward)—, if there is a heaven, I know there is no welcome for me there. For I have been unfaithful to my love, having sated my hunger and desire with others. At first I was ashamed and cursed myself for my weakness, but then I realized that I could not help myself. I was at the mercy of a compulsion. Once you have known such desire, you must satisfy the craving. There is no denying it. Once you have drunk from the wellspring, from the fountain of youth, you must quench your thirst again and again, or you age more rapidly than if you had not known love in the first instance. If you are a passionate being as I am, you cannot live without it. It is an addiction.

I trust I am not shocking you. I have been alone for so long I have become somewhat indifferent to the sensibilities of others. And besides I have not entertained a guest – not since…

…but it has not always been so. In my youth I had a most enviable reputation as a socialite and a gracious host renowned for my lavish soirees on which I spent a considerable part of my not inconsiderable fortune. The remainder I squandered in empty and extravagant revelries after my bereavement in a vain effort to assuage my grief.

And over the ensuing years as my house fell into disrepair my fortune depleted to the point where I now condescend to accept employment to keep body and soul together. Yes, as demeaning as it is to one of my station, I have acceded to necessity and now ply a trade of sorts.

(SELF-DEPRECATING LAUGH)

And inevitably, the years have also taken their toll upon my body as they did upon my house. I have aged and decayed none too well, I confess. But I bear up. A little rouge to bring a blush to these pallid cheeks, a touch of greasepaint to mask the lines etched in my face and I have taken twenty years off my life. Ah, if only–

(PAUSES)

You remain unmoved? Greedily recording my confession in that immaculate copperplate hand that betrays a clinical detachment to the specimen you have chosen to study. But then this admission is precisely what you have travelled so far to hear, is it not? And, after all, I have much to confess.

How I envy you, your life among the gay whirl of society. And would gladly exchange it for my seclusion were it not for the bitter sweet memory of that love I speak of. The love that haunts me. I know that I am doomed to live alone and estranged from bustling humanity. I have paid a most dreadful price for my dissolute ways and excesses, but now I must endure the solitude that only the insane and the inconsolable must suffer. To experience the bitter-sweet longing of love and lose it once is torture, but to suffer the loss over and over again, as I have in my vain attempts to relive the one great love of my life, is a pain that gnaws at the very fabric of my being, at the burning ember that is all that remains of my soul.

(BITTER LAUGHTER)

But here I am again, playing to the gallery, wringing every wretched line of this pathetic melodrama that has been my life. And for whom? An audience of one. I think it best that we part here, my friend. I am due to take the stage in a few minutes. You have seen my act once and I must confess, I stick pretty much to the same ‘business’ every performance. The locals are easily amused. They leer at the lithesome dancers in the neighbouring tent and they stare like frightened children at the exhibits, our carnival of horrors, our circus of freaks of which I—it appears—am the principal attraction. But once a man of the legitimate theatre, such as yourself, has seen our tawdry little entertainment, there is no profit in sitting through it again.

So I bid you farewell and a safe journey back to England. I trust you enjoyed your stay in our country. Oh, and good luck with your book, should you finish it. Though I’m still not convinced that your choice of title is a wise one. You would be better using my real name. Though I must say, I cannot imagine those genteel ladies of London pouring over such horrors no matter what title you give it. You’ll be hounded from your lodgings before the ink on the first reviews are dry.

Mark my words, Mr Stoker, you will regret the day you met me.

© Paul Roland 2013